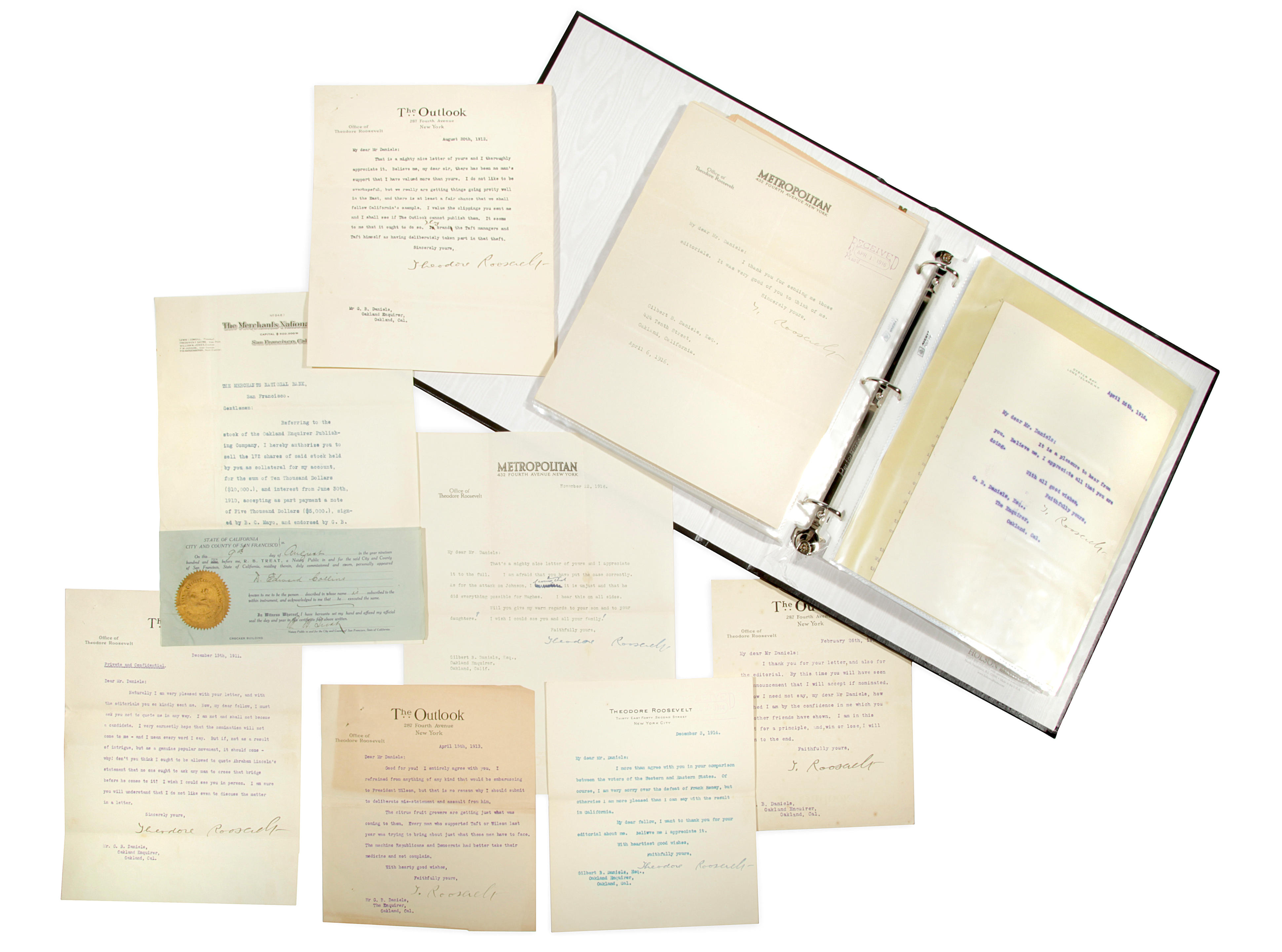

Roosevelt, TheodoreA collection of ten typed letters signed, including four by Theodore Roosevelt, regarding the founding of the Progressive Party 10 typed letters signed, 1912–1924, all to Paul A. Ewert, 5 by Roosevelt, 2 by Hiram Johnson, and one each by Warren G. Harding, George W. Perkins, and Herbert S. Hadley, many with autograph emendations, a few accompanied by original envelopes; together with 5 retained typed copies of letters by Ewart, the Ewart copies browned and brittle. Housed in a red morocco portfolio gilt, within a half red morocco folding-box. The Foundation of the Progressive Party, one of the earliest and most successful third-party launches in American political history. The Progressive Party, also popularly known as the Bull Moose, was founded by former president Theodore Roosevelt when he decided that he wanted another term in the White House after all, after stepping aside in 1908 in favor of his Secretary of War, William Howard Taft. Taft refused to relinquish control of the Republican convention, which selected him as the GOP standard bearer. Taking Governor Hiram Johnson of California as a running-mate, TR ran as a third-party candidate, and while he outpolled Taft, in doing so he split the Republican vote and threw the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. The most significant of these letters, all of which were directed to Paul Ewart, a Progressive Party organizer in Missouri, is from Roosevelt, 5 July 1912, and runs to six heavily corrected pages. In this letter Roosevelt defends both his decision to bolt the Republican party and his personal behavior. As to the first charge, Roosevelt argues that his challenge had less to do with securing the nomination for himself than with making sure the convention delegates had been purged of Taft's political cronies. He points out that other party leaders, including Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, had expressed similar concerns. He then moves on to address at greater length the "criminal libel" of his drinking to excess. "On the day I spoke at Osawatomie I did not touch a drop of anything stronger than coffee or tea; I know this because on those trips I do not drink at all. On the Mississippi trip it is possible, although not probable, that if they had white wine at dinner on the boat, I may have taken a glass. … I never drink beer; I never touch whisky; I have never drunk a highball or cocktail in my life. I never, at St. Louis or anywhere, drank any whisky unless it was on a prescription. … I usually have sherry or Madera or white wine at my table if there are guests. … And I always have it when Methodist bishops visit me, just because I don't want anyone to think that I am hypocritical." After continuing in this vein for another half page, Roosevelt concludes, "There! I don't know how I could make that point any straighter," before adding in holograph, "I have never been in the slightest degree under the influence of liquor." Roosevelt next offers a frank assessment of his candidacy. "Nothing has touched me more than the willingness of men in whom I earnestly believe to leave their offcial positions and come out in this fight. But in such a case I feel that the sacrifice ought not to be made unless the good that will be done out weighs the damage that will also be done. It is a good deal now as it was when I went to the war—I refused to take into my regiment any married man who was depending on his own exertions for the livelihood of his wife and children. … I did not feel that the emergency justified the sacrifice of the man's family. In the same way, just at present I do not feel that our cause is sufficiently bright to warrant me in having men like you … come out for me. … The probabilities are against success." In a later letter after the election, 11 November 1912, Roosevelt seems to reflect on the future of the Progressive Party: "We must organize now, and get together. We must try to get newspapers; but, my dear fellow, all that means money

Roosevelt, TheodoreA collection of ten typed letters signed, including four by Theodore Roosevelt, regarding the founding of the Progressive Party 10 typed letters signed, 1912–1924, all to Paul A. Ewert, 5 by Roosevelt, 2 by Hiram Johnson, and one each by Warren G. Harding, George W. Perkins, and Herbert S. Hadley, many with autograph emendations, a few accompanied by original envelopes; together with 5 retained typed copies of letters by Ewart, the Ewart copies browned and brittle. Housed in a red morocco portfolio gilt, within a half red morocco folding-box. The Foundation of the Progressive Party, one of the earliest and most successful third-party launches in American political history. The Progressive Party, also popularly known as the Bull Moose, was founded by former president Theodore Roosevelt when he decided that he wanted another term in the White House after all, after stepping aside in 1908 in favor of his Secretary of War, William Howard Taft. Taft refused to relinquish control of the Republican convention, which selected him as the GOP standard bearer. Taking Governor Hiram Johnson of California as a running-mate, TR ran as a third-party candidate, and while he outpolled Taft, in doing so he split the Republican vote and threw the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. The most significant of these letters, all of which were directed to Paul Ewart, a Progressive Party organizer in Missouri, is from Roosevelt, 5 July 1912, and runs to six heavily corrected pages. In this letter Roosevelt defends both his decision to bolt the Republican party and his personal behavior. As to the first charge, Roosevelt argues that his challenge had less to do with securing the nomination for himself than with making sure the convention delegates had been purged of Taft's political cronies. He points out that other party leaders, including Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, had expressed similar concerns. He then moves on to address at greater length the "criminal libel" of his drinking to excess. "On the day I spoke at Osawatomie I did not touch a drop of anything stronger than coffee or tea; I know this because on those trips I do not drink at all. On the Mississippi trip it is possible, although not probable, that if they had white wine at dinner on the boat, I may have taken a glass. … I never drink beer; I never touch whisky; I have never drunk a highball or cocktail in my life. I never, at St. Louis or anywhere, drank any whisky unless it was on a prescription. … I usually have sherry or Madera or white wine at my table if there are guests. … And I always have it when Methodist bishops visit me, just because I don't want anyone to think that I am hypocritical." After continuing in this vein for another half page, Roosevelt concludes, "There! I don't know how I could make that point any straighter," before adding in holograph, "I have never been in the slightest degree under the influence of liquor." Roosevelt next offers a frank assessment of his candidacy. "Nothing has touched me more than the willingness of men in whom I earnestly believe to leave their offcial positions and come out in this fight. But in such a case I feel that the sacrifice ought not to be made unless the good that will be done out weighs the damage that will also be done. It is a good deal now as it was when I went to the war—I refused to take into my regiment any married man who was depending on his own exertions for the livelihood of his wife and children. … I did not feel that the emergency justified the sacrifice of the man's family. In the same way, just at present I do not feel that our cause is sufficiently bright to warrant me in having men like you … come out for me. … The probabilities are against success." In a later letter after the election, 11 November 1912, Roosevelt seems to reflect on the future of the Progressive Party: "We must organize now, and get together. We must try to get newspapers; but, my dear fellow, all that means money

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert