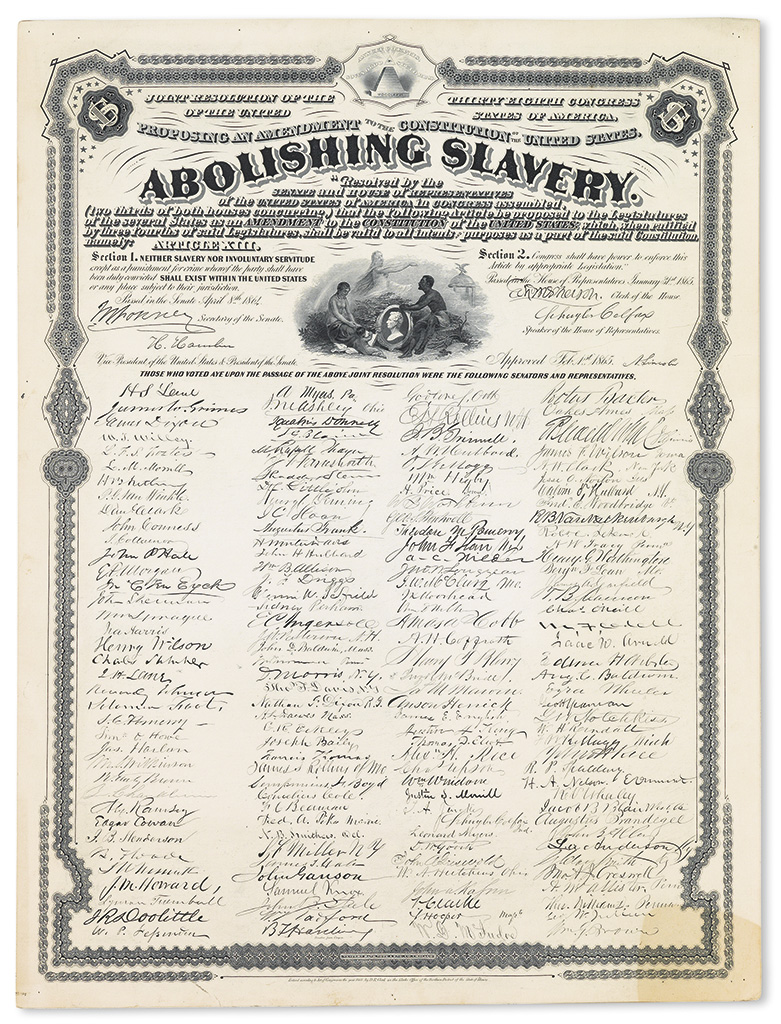

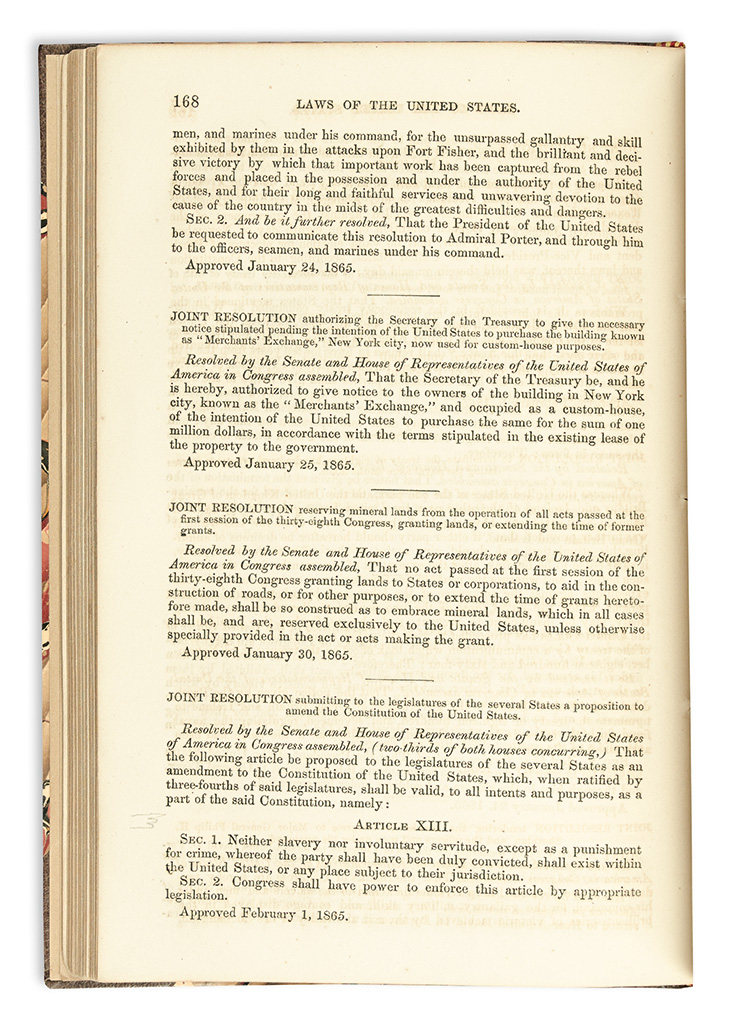

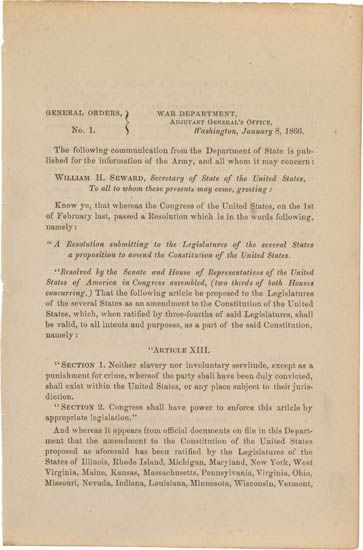

LINCOLN, Abraham. THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT. UNITED STATES, 38TH CONGRESS. Manuscript document signed ("Abraham Lincoln") as President, comprising the text of the Thirteenth Amendment as a Joint Resolution to Amend the Constitution, submitted to the States for Ratification, also signed by Vice President H. Hamlin, Schuyler Colfax and J.W. Forney (Speaker and Secretary respectively of the Senate) and 38 Senators and 114 members of the House of Representatives. [Washington, D.C.,] 1 February 1865. Large folio (20 5/8 x 15 3/8 in.). FINELY ENGROSSED IN INK ON PARCHMENT. Within a dark blue line border, the bold calligraphic heading "Thirty-Eight Congress of the United States, A Resolution Submitting to the Legislatures of the Several States a proposition to amend the Constitution of the United States," followed by the full text of the resolution, and "Article XIII," beneath, the ink signatures of "J.W. Forney, "Schuyler Colfax," "H. Hamlin," and at the right, "Approved February 1 1865 Abraham Lincoln." Below are the signatures of the Senators and Congressmen, arranged in two groups and disposed in five neatly ruled columns. Lincoln's signature dark and clear, the text very readable, the vellum without the usual soiling or marginal defects. "NEITHER SLAVERY NOR INVOLUNTARY SERVITUDE SHALL EXIST WITHIN THE UNITED STATES": ONE OF 13 EXAMPLES OF THE 13TH AMENDMENT SIGNED BY PRESIDENT LINCOLN, ONE OF THE FINEST EXTANT COPIES AND ONE OF THE LAST STILL IN PRIVATE HANDS Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servi- tude, except as a punishment of crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted shall exist in the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. One of the finest known Congressional copies of the 13th Amendment Resolution, boldly signed by Lincoln in testimony to his role as its architect, his unswerving committment to its ratification, and his profound dedication to the fundamental moral principle that it embodies. During the course of the Civil War, the struggle for the universal and permanent abolition of slavery evolved from the avowed end of a small, vocal minority--the abolitionists--to become, through Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, a crucial and revolutionary part of the President's and the Union's military strategy. And finally, it became a war aim in itself when the Republican platform of 1864 boldly called for an Amendment to the Constitution prohibiting slavery, terming it a practice "hostile to the principles of republican government, justice and national safety." In the end, "it was the outcome of the war," James M. McPherson writes, "that transformed and expanded the concept of liberty to include abolition of slavery, and it was Lincoln who was the principal agent of this transformation" ("Lincoln and Liberty," in Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, p.45). Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief issued the Emancipation Proclamation-- theoretically freeing slaves in the territories then in rebellion--as a military measure, recognizing that it was not within the power of his office to summarily abolish slavery throughout the nation. That definitive act, Lincoln rightly believed, required a Constitutional amendment. Resolutions calling for such an amendment were drafted in the Republican-controlled Senate as early as April 1864; the final version, largely the work of Connecticut Senator Lyman Trumbull, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, adopted wording strikingly similar to that drafted by Jefferson in 1787 for the Northwest Ordinance, prohibiting slavery in the new territories of the northwest. The Senate passed the resolution quickly, on a vote of 38 to 6, but in the House of Representatives, with tenacious opposition from Democrats, it was defeated in balloting on June 15, 1864. So matters rested until the critical November elections. Then, in the wake of important Union victories on

LINCOLN, Abraham. THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT. UNITED STATES, 38TH CONGRESS. Manuscript document signed ("Abraham Lincoln") as President, comprising the text of the Thirteenth Amendment as a Joint Resolution to Amend the Constitution, submitted to the States for Ratification, also signed by Vice President H. Hamlin, Schuyler Colfax and J.W. Forney (Speaker and Secretary respectively of the Senate) and 38 Senators and 114 members of the House of Representatives. [Washington, D.C.,] 1 February 1865. Large folio (20 5/8 x 15 3/8 in.). FINELY ENGROSSED IN INK ON PARCHMENT. Within a dark blue line border, the bold calligraphic heading "Thirty-Eight Congress of the United States, A Resolution Submitting to the Legislatures of the Several States a proposition to amend the Constitution of the United States," followed by the full text of the resolution, and "Article XIII," beneath, the ink signatures of "J.W. Forney, "Schuyler Colfax," "H. Hamlin," and at the right, "Approved February 1 1865 Abraham Lincoln." Below are the signatures of the Senators and Congressmen, arranged in two groups and disposed in five neatly ruled columns. Lincoln's signature dark and clear, the text very readable, the vellum without the usual soiling or marginal defects. "NEITHER SLAVERY NOR INVOLUNTARY SERVITUDE SHALL EXIST WITHIN THE UNITED STATES": ONE OF 13 EXAMPLES OF THE 13TH AMENDMENT SIGNED BY PRESIDENT LINCOLN, ONE OF THE FINEST EXTANT COPIES AND ONE OF THE LAST STILL IN PRIVATE HANDS Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servi- tude, except as a punishment of crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted shall exist in the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. One of the finest known Congressional copies of the 13th Amendment Resolution, boldly signed by Lincoln in testimony to his role as its architect, his unswerving committment to its ratification, and his profound dedication to the fundamental moral principle that it embodies. During the course of the Civil War, the struggle for the universal and permanent abolition of slavery evolved from the avowed end of a small, vocal minority--the abolitionists--to become, through Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, a crucial and revolutionary part of the President's and the Union's military strategy. And finally, it became a war aim in itself when the Republican platform of 1864 boldly called for an Amendment to the Constitution prohibiting slavery, terming it a practice "hostile to the principles of republican government, justice and national safety." In the end, "it was the outcome of the war," James M. McPherson writes, "that transformed and expanded the concept of liberty to include abolition of slavery, and it was Lincoln who was the principal agent of this transformation" ("Lincoln and Liberty," in Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, p.45). Lincoln as Commander-in-Chief issued the Emancipation Proclamation-- theoretically freeing slaves in the territories then in rebellion--as a military measure, recognizing that it was not within the power of his office to summarily abolish slavery throughout the nation. That definitive act, Lincoln rightly believed, required a Constitutional amendment. Resolutions calling for such an amendment were drafted in the Republican-controlled Senate as early as April 1864; the final version, largely the work of Connecticut Senator Lyman Trumbull, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, adopted wording strikingly similar to that drafted by Jefferson in 1787 for the Northwest Ordinance, prohibiting slavery in the new territories of the northwest. The Senate passed the resolution quickly, on a vote of 38 to 6, but in the House of Representatives, with tenacious opposition from Democrats, it was defeated in balloting on June 15, 1864. So matters rested until the critical November elections. Then, in the wake of important Union victories on

.jpg)

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen