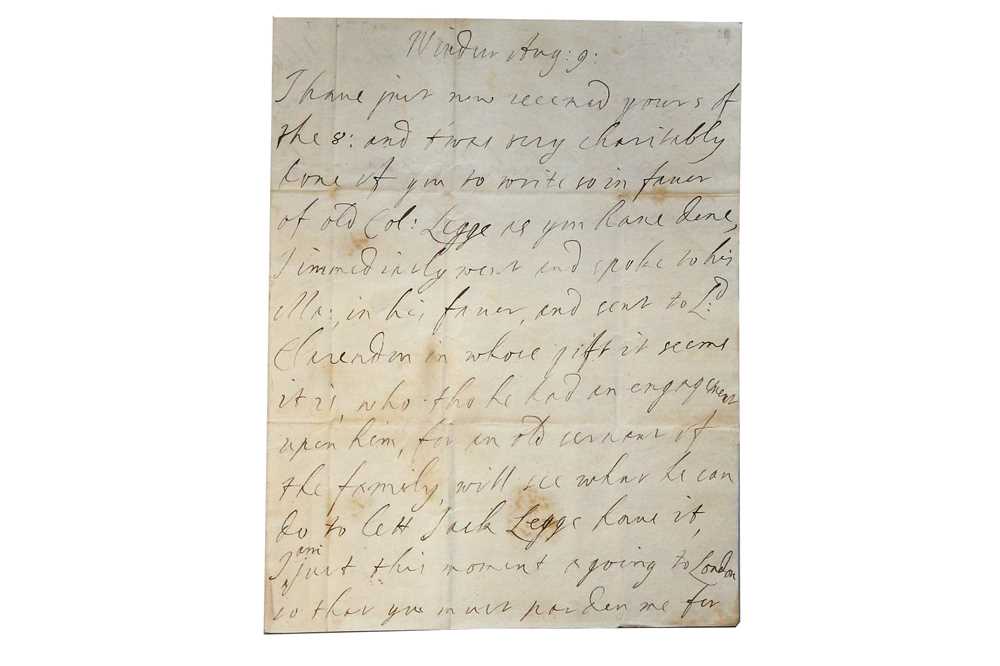

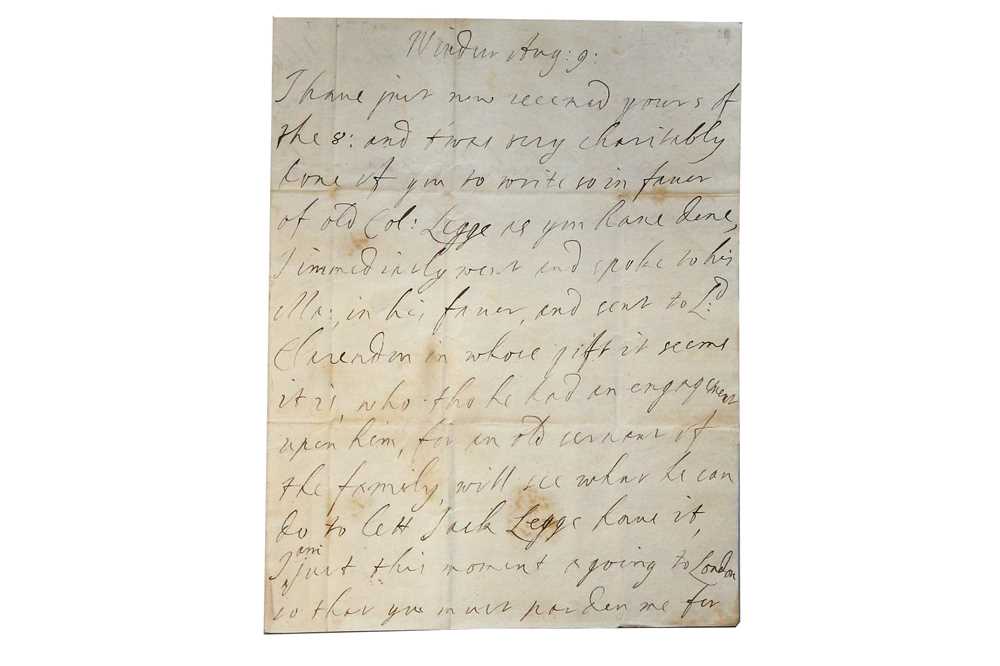

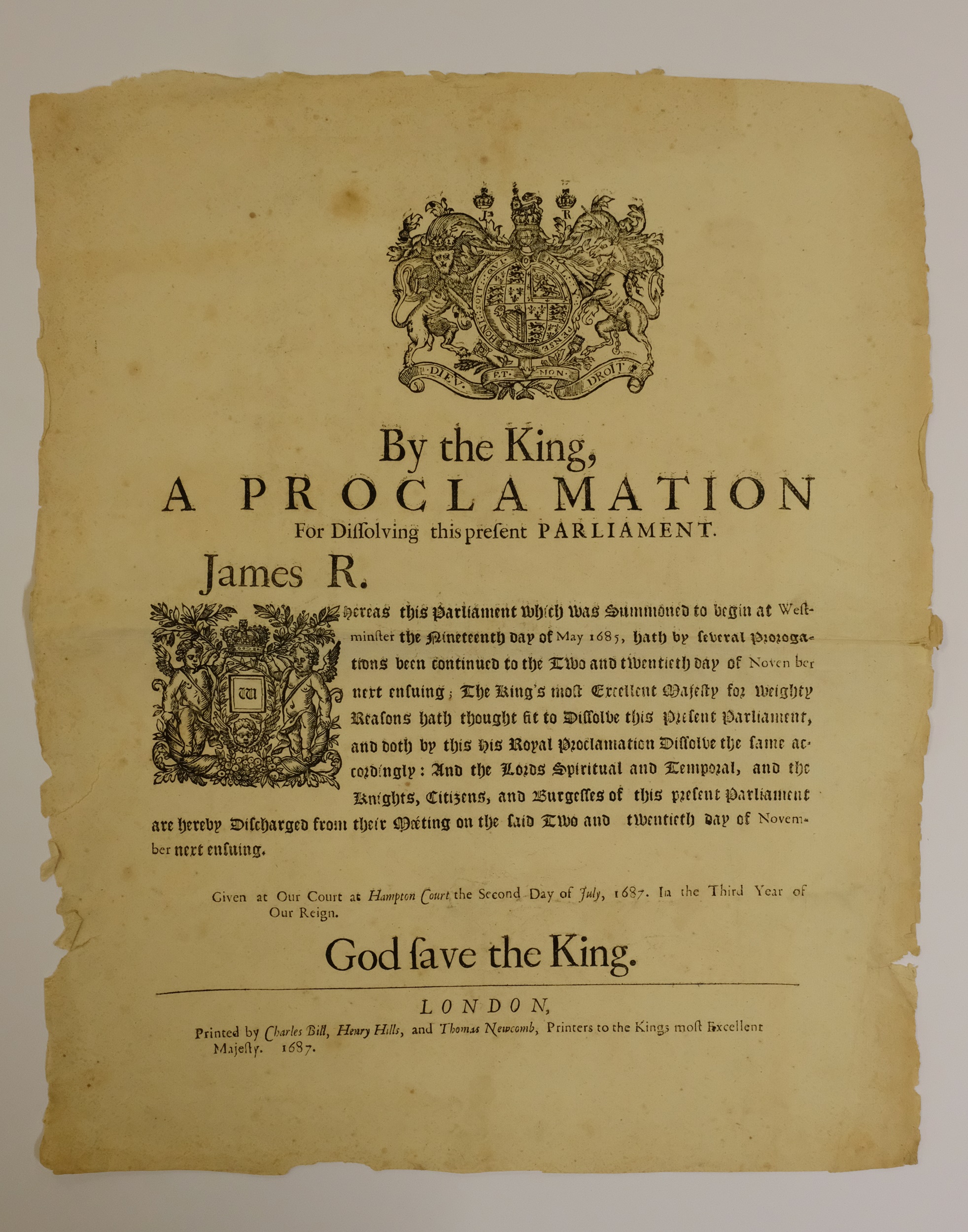

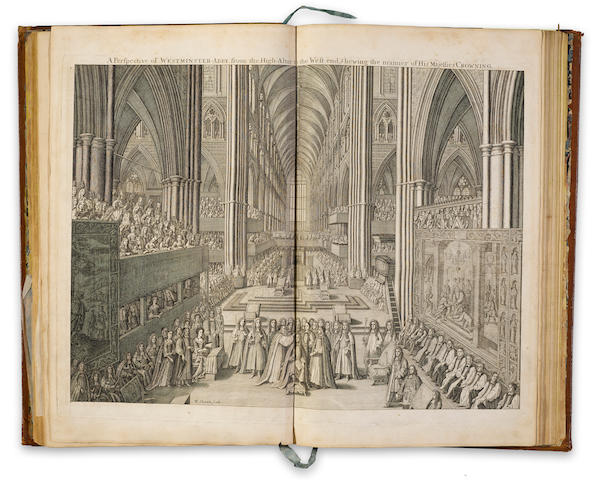

JAMES II (1633-1701), King of England. A series of 54 autograph letters signed (as Duke of York, with initial 'J') to William, Prince of Orange (his son in law, and successor as King William III of England, 1688-1702), London (21), Brussels (26), Windsor (4), Hatfield, Newark and Edinburgh, 29 October [1678] - 27 November [1679], 126 pages, 4to , autograph address leaves ('For my sonne the Prince of Orange'), seals (occasional light spotting and duststains, small seal tears, letter of 7 October [1679] endorsed in an 18th-century hand); and a secretarial copy of a letter by Charles II to his sister [Elizabeth, the Electress Palatine], Hampton Court, 20 December 1636, one page, 4to , the letters tipped on guards into an album, 19th-century calf (scuffed); bookplate of G[eorge] S[avile] Foljambe.

JAMES II (1633-1701), King of England. A series of 54 autograph letters signed (as Duke of York, with initial 'J') to William, Prince of Orange (his son in law, and successor as King William III of England, 1688-1702), London (21), Brussels (26), Windsor (4), Hatfield, Newark and Edinburgh, 29 October [1678] - 27 November [1679], 126 pages, 4to , autograph address leaves ('For my sonne the Prince of Orange'), seals (occasional light spotting and duststains, small seal tears, letter of 7 October [1679] endorsed in an 18th-century hand); and a secretarial copy of a letter by Charles II to his sister [Elizabeth, the Electress Palatine], Hampton Court, 20 December 1636, one page, 4to , the letters tipped on guards into an album, 19th-century calf (scuffed); bookplate of G[eorge] S[avile] Foljambe. A revealing and surprisingly cordial series of letters written to his son-in-law -- the defender of Protestantism -- during the twelve months when widespread suspicion and unease about the future governance of England in the light of the Duke of York's marriage to the Catholic Mary of Modena and his own conversion to Roman Catholicism had exploded in September 1678 in Titus Oates' fabrication of the 'Popish Plot' to kill the King. James's importance as heir presumptive was the consequence of Charles II's failure to produce a legitimate son. The rallying of support for the Earl of Shaftesbury's Exclusion Bill to remove the Duke of York from the succession -- the background to many of the letters -- appeared to threaten the principle of hereditary monarchy. Although clauses in the Test Act exempted its provisions from applying to James, the perceived danger from his presence led to his banishment to the Spanish Netherlands for six months in 1679, during which he sent off a stream of letters to his son-in-law and his friends expressing his anxieties and particularly his concerns about the Duke of Monmouth (Charles II's natural son by Lucy Walters), whose ambitions the King appeared to indulge. James returned to England when the King was thought to be dangerously ill, but on Charles's recovery, and Monmouth's disgrace, he was hastily removed from the centre of events and appointed Viceroy in Scotland: the last of the present letters is dated from Edinburgh. 'When [Oates] will make an end of accusing people the Lord knows, but their chief malice is against me, for they think they have no so sure way of ruining the King, as begining with me. This day Lord Shaf[te]sbury and his gange shewd their malice to me and would have gott a thing done that might have proved very prejuditial to me, but they could not carry it in our House' (29 October 1678). 'I have gott a proviso added to the bill for puting the Catholike Lords out of the House and banishing all of that perswation from the Court, that nothing in that act shall extend to me; so that in this my enemys have mist of their aime, for their cheef designe by this bill, was to drive me from his Majesty's presence ... yett their malice to me continus as much and more then ever, and thay have [a] new designe on foott against me, and I am sure will leave no stone unturned to ruine me if they can so that I am far from being secure, by having gaind that point yesterday' (22 November 1678). Several letters of May 1679 contain dire predictions of the dangers from Shaftesbury's appointment as President of the Council, and of the Presbyterians' probable support for the Duke of Monmouth in order to destroy the monarchy: '[I] cannot now but looke on the monarky ist [sic] self in great danger as well as his Majesty's person, and that not from Papists but from the Commonwelth party and some of those who were latly brought into the Councell that gouverne the Duke of Monmouth and who make a property of him to ruine our family'. The King's indecision prompts the hope that 'this [the Exclusion Bill] and some other procedings of the Commons will have so allarumd his Majesty and the Lords, that he will at last t

JAMES II (1633-1701), King of England. A series of 54 autograph letters signed (as Duke of York, with initial 'J') to William, Prince of Orange (his son in law, and successor as King William III of England, 1688-1702), London (21), Brussels (26), Windsor (4), Hatfield, Newark and Edinburgh, 29 October [1678] - 27 November [1679], 126 pages, 4to , autograph address leaves ('For my sonne the Prince of Orange'), seals (occasional light spotting and duststains, small seal tears, letter of 7 October [1679] endorsed in an 18th-century hand); and a secretarial copy of a letter by Charles II to his sister [Elizabeth, the Electress Palatine], Hampton Court, 20 December 1636, one page, 4to , the letters tipped on guards into an album, 19th-century calf (scuffed); bookplate of G[eorge] S[avile] Foljambe.

JAMES II (1633-1701), King of England. A series of 54 autograph letters signed (as Duke of York, with initial 'J') to William, Prince of Orange (his son in law, and successor as King William III of England, 1688-1702), London (21), Brussels (26), Windsor (4), Hatfield, Newark and Edinburgh, 29 October [1678] - 27 November [1679], 126 pages, 4to , autograph address leaves ('For my sonne the Prince of Orange'), seals (occasional light spotting and duststains, small seal tears, letter of 7 October [1679] endorsed in an 18th-century hand); and a secretarial copy of a letter by Charles II to his sister [Elizabeth, the Electress Palatine], Hampton Court, 20 December 1636, one page, 4to , the letters tipped on guards into an album, 19th-century calf (scuffed); bookplate of G[eorge] S[avile] Foljambe. A revealing and surprisingly cordial series of letters written to his son-in-law -- the defender of Protestantism -- during the twelve months when widespread suspicion and unease about the future governance of England in the light of the Duke of York's marriage to the Catholic Mary of Modena and his own conversion to Roman Catholicism had exploded in September 1678 in Titus Oates' fabrication of the 'Popish Plot' to kill the King. James's importance as heir presumptive was the consequence of Charles II's failure to produce a legitimate son. The rallying of support for the Earl of Shaftesbury's Exclusion Bill to remove the Duke of York from the succession -- the background to many of the letters -- appeared to threaten the principle of hereditary monarchy. Although clauses in the Test Act exempted its provisions from applying to James, the perceived danger from his presence led to his banishment to the Spanish Netherlands for six months in 1679, during which he sent off a stream of letters to his son-in-law and his friends expressing his anxieties and particularly his concerns about the Duke of Monmouth (Charles II's natural son by Lucy Walters), whose ambitions the King appeared to indulge. James returned to England when the King was thought to be dangerously ill, but on Charles's recovery, and Monmouth's disgrace, he was hastily removed from the centre of events and appointed Viceroy in Scotland: the last of the present letters is dated from Edinburgh. 'When [Oates] will make an end of accusing people the Lord knows, but their chief malice is against me, for they think they have no so sure way of ruining the King, as begining with me. This day Lord Shaf[te]sbury and his gange shewd their malice to me and would have gott a thing done that might have proved very prejuditial to me, but they could not carry it in our House' (29 October 1678). 'I have gott a proviso added to the bill for puting the Catholike Lords out of the House and banishing all of that perswation from the Court, that nothing in that act shall extend to me; so that in this my enemys have mist of their aime, for their cheef designe by this bill, was to drive me from his Majesty's presence ... yett their malice to me continus as much and more then ever, and thay have [a] new designe on foott against me, and I am sure will leave no stone unturned to ruine me if they can so that I am far from being secure, by having gaind that point yesterday' (22 November 1678). Several letters of May 1679 contain dire predictions of the dangers from Shaftesbury's appointment as President of the Council, and of the Presbyterians' probable support for the Duke of Monmouth in order to destroy the monarchy: '[I] cannot now but looke on the monarky ist [sic] self in great danger as well as his Majesty's person, and that not from Papists but from the Commonwelth party and some of those who were latly brought into the Councell that gouverne the Duke of Monmouth and who make a property of him to ruine our family'. The King's indecision prompts the hope that 'this [the Exclusion Bill] and some other procedings of the Commons will have so allarumd his Majesty and the Lords, that he will at last t

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen