Details

Defending his reputation to his future father-in-law

Mark Twain, 29 December [1868]

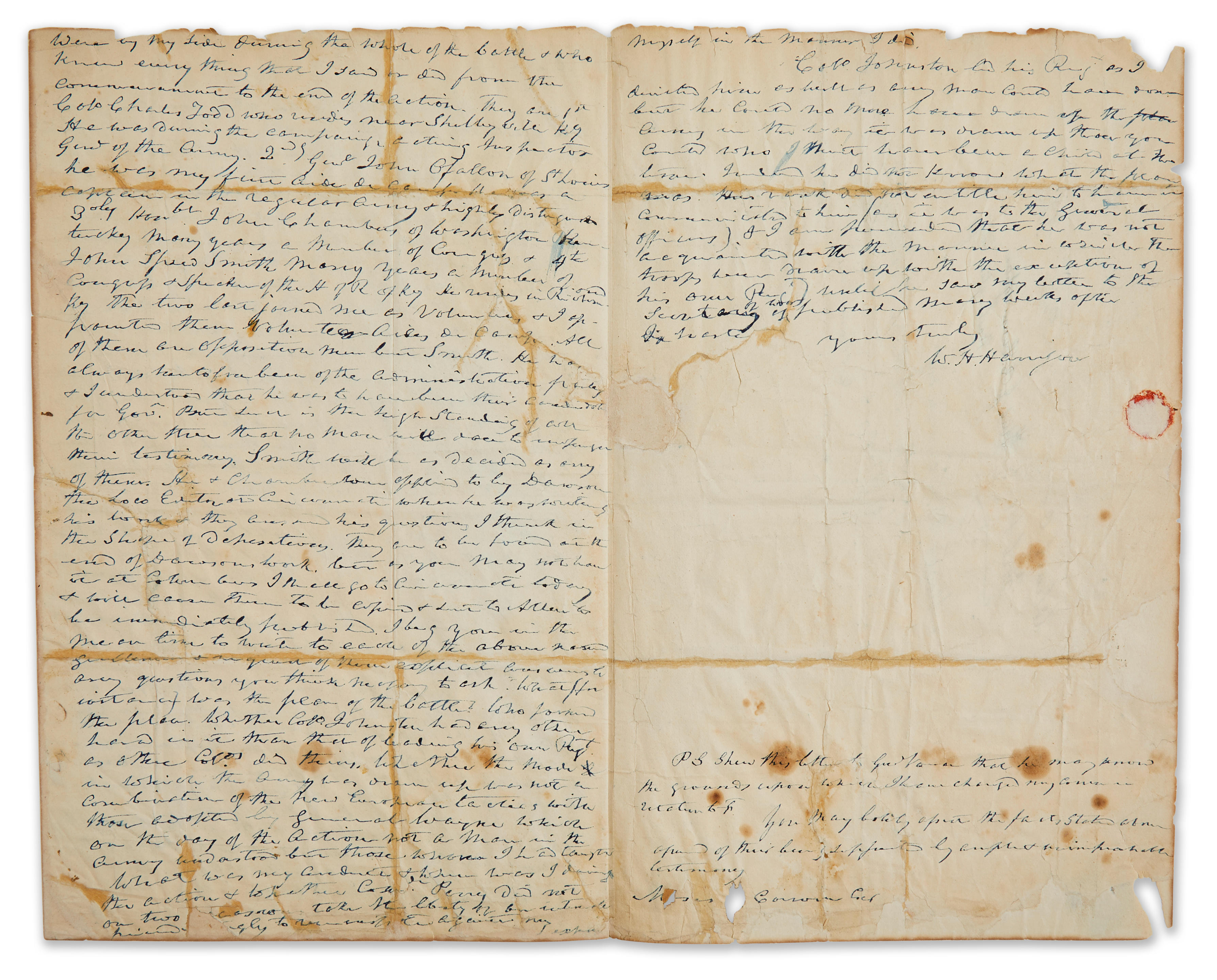

CLEMENS, Samuel ("Mark Twain," 1835-1910). Autograph letter signed ("Saml'l L. Clemens") to Jervis Langdon, 29 December [1868].

Nine pages, 205 x 128mm, addressed in his hand on the verso of the final leaf with penciled docketing in Langdon's[?] hand. Blue cloth clamshell.

"What I have been, what I am, and what I am likely to be." Clemens defends his character to his skeptical future father-in-law, Jervis Langdon. A letter remarkable for its length, its content, and its critical importance to the young writer. Although already engaged to Livy Langdon, her parents remained skeptical of Clemens given his line of work, his associates, and his penchant for irreverence (most notably toward Christianity), leading to demands for character references. While on a lecture tour in Michigan, Clemens received a letter bearing a harsh rebuke from Jervis over an awkward incident in the family's Elmira, New York drawing room in late November. Treading lightly, Clemens explains, "I will not deny that the first paragraph hurt me a little—hurt me a good deal—for when you speak of what I said of the drawing-room, I see you mistook the harmless overflow of a happy frame of mind for criminal frivolity. This is a little unjust—for although what I said may have been unbecoming, it surely was no worse. The subject of the drawing-room cannot be more serious to you than it is to me. But I accept the rebuke, freely & without offer of defence & am as sorry I offended as if I had intended offence." To the balance of Langdon's letter, "is just as it should be. The language is as plain as ever language was in the world, but I like it all the better for that. I don't like to mince matters myself or have them minced for me. I think I am safely past that tender age when one cannot take his food save that it be masticated for him beforehand."

"I am not hurrying my love—it is my love that is hurrying me—& surely no one is better able to comprehend that than you." The Langdons had been taken aback by the suddenness of their daughter's engagement to the young author, which led them to suspect Clemens was rash and immoderate. "I fancy that Mrs. Langdon was the counter part of her daughter at the age of twenty-three—& so I refer you to the past for explanation & for pardon of my conduct. At your time of life, & being, like you, the object of an assured regard, I shall be able to urge moderation upon younger people, & shall do it relentlessly—but now I feel a larger charity for such. Your heart is big enough to feel all the force of that remark.—& so believing, you will not be surprised to find me thus boldly knocking at it. It does not seem to me that I am otherwise than moderate—it cannot seem so from my point of view—& so while I continue as moderate as I am now & have been, I think it is fair to hope that you will not turn away from me your countenance, or deny me your friendly toleration, even though it be under a mild protest."

"It is my desire as truly as yours, that sufficient time shall elapse to show you, beyond all possible question, what I have been, what I am, & what I am likely to be. Otherwise you could not be satisfied with me, nor I with myself." In defending his character, he cites his time on the West Coast and Hawaii, where his immersion into the local native culture led to additional doubts on the part of the Langdons: "I think that much of my conduct on the Pacific Coast was not of a character to recommend me to the respectful regard of a high eastern civilization, but it was not considered blameworthy there, perhaps. We go according to our lights. […] I think all my references can say I never did anything mean, false or criminal. They can say that the same doors that were open to me seven years ago are open to me yet; that all the friends I made in seven years, are still my friends; that wherever I have been I can go again—& enter in the light of day & hold my head up; that I never deceived or defrauded anybody, & don’t owe a cent. And they can say that I attended to my business with due diligence, & made my own living, & never asked anybody to help me do it, either. All the rest they can say about me will be bad. I can tell the whole story myself, without mincing it, & will if they refuse."

Clemens requests to "add to the references I gave Mrs. Langdon," providing a lengthy list off the many "friends" he made out west, including John Neely Johnson (1725-1872) of Carson City, Nevada ("was Governor of California some ten years ago & is now Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Nevada" and for some time his next door neighbor; Henry Goode Blasdel (1825-1900), the first governor of Nevada ("he has known me four or five years—don’t know whether he has known any good of me or not. He is a thoroughly pure & upright man"); Joseph T. Goodman, ("raised in Elmira, I belive … Chief editor of the 'Daily Enterprise', Virginia City") and Goodman's News-Editor, Putnam ("neither of whom would say a damaging word against me for love or money or hesitate to throttle anybody else who ventured to do it…"). In addition, Clemens refers Langdon to Lewis Leland (a hotel proprietor in New York, formerly of san Francisco's Occidental), and R. B. Swain of the San Francisco Mint: "the Schuyler Colfax of the Pacific Coast," a man "against whose pure reputation nothing can be said, although Clemens confesses, "he don't know much about me himself, but he ought to know a good deal through his secretary Frank B. [Bret] Harte (Editor of the Overland Monthly & the finest writer out there)" [Clemens has crossed out "one of the finest writers out there"] for we have been intimate for several years…" Quoting this portion of the letter, Justin Kaplan comments that "it was a curiously random, even self-defeating list … Clemens later said that he had left out close friends because he knew they would lie for him" (Kaplan, Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain, p. 90).

"As to what I am going to be, henceforth, it is a thing which must be proven & I am upon the right path—I shall succeed, I hope. Men as lost as l, have found a Saviour, & why not l? I have hope—an earnest hope—a long-lived hope" [a passage probably elicited by Langdon's criticism of instability and Clemens's rather inchoate religious beliefs]. Clemens offers additional details regarding his continuing lecture tour, his salary, and plans being considered to take over a Cleveland newspaper, then concludes by asking "pardon for past offences against yourself, they having been heedless, & not deliberate.. . He signs himself "With reverent love & respect."

The outcome is best narrated by Clemens himself. In early 1869, Mr. Langdon began to receive replies from the people he had been directed to by Clemens. "The results were not promising. All those men Were frank to a fault. They not only spoke in disapproval of me but they were quite unnecessarily and exaggeratedly enthusiastic about it. " When he and Jervis Langdon met to discuss the unflattering letters of reference, Langdon exclaimed, "'What kind of friends are these? Haven't you a friend in the world?' 'Apparently not,' I answered. 'Then he said: 'I'll be your friend myself. Take the girl. I know you better than they do.' Thus dramatically and happily was my fate settled" (The Autobiography of Mark Twain, ed. Charles Nieder, 1966, pp. 106-107). Published in The Love Letters of Mark Twain, ed. Dixon Wector, New York, 1949. Provenance: Clara Clemens Samossoud – Chester L. Davis (sale, Christie's New York, 17 May 1991, lot 82) – James S. Copley Library (sale, Sotheby's, New York, 17 June 2010, lot 461).

Details

Defending his reputation to his future father-in-law

Mark Twain, 29 December [1868]

CLEMENS, Samuel ("Mark Twain," 1835-1910). Autograph letter signed ("Saml'l L. Clemens") to Jervis Langdon, 29 December [1868].

Nine pages, 205 x 128mm, addressed in his hand on the verso of the final leaf with penciled docketing in Langdon's[?] hand. Blue cloth clamshell.

"What I have been, what I am, and what I am likely to be." Clemens defends his character to his skeptical future father-in-law, Jervis Langdon. A letter remarkable for its length, its content, and its critical importance to the young writer. Although already engaged to Livy Langdon, her parents remained skeptical of Clemens given his line of work, his associates, and his penchant for irreverence (most notably toward Christianity), leading to demands for character references. While on a lecture tour in Michigan, Clemens received a letter bearing a harsh rebuke from Jervis over an awkward incident in the family's Elmira, New York drawing room in late November. Treading lightly, Clemens explains, "I will not deny that the first paragraph hurt me a little—hurt me a good deal—for when you speak of what I said of the drawing-room, I see you mistook the harmless overflow of a happy frame of mind for criminal frivolity. This is a little unjust—for although what I said may have been unbecoming, it surely was no worse. The subject of the drawing-room cannot be more serious to you than it is to me. But I accept the rebuke, freely & without offer of defence & am as sorry I offended as if I had intended offence." To the balance of Langdon's letter, "is just as it should be. The language is as plain as ever language was in the world, but I like it all the better for that. I don't like to mince matters myself or have them minced for me. I think I am safely past that tender age when one cannot take his food save that it be masticated for him beforehand."

"I am not hurrying my love—it is my love that is hurrying me—& surely no one is better able to comprehend that than you." The Langdons had been taken aback by the suddenness of their daughter's engagement to the young author, which led them to suspect Clemens was rash and immoderate. "I fancy that Mrs. Langdon was the counter part of her daughter at the age of twenty-three—& so I refer you to the past for explanation & for pardon of my conduct. At your time of life, & being, like you, the object of an assured regard, I shall be able to urge moderation upon younger people, & shall do it relentlessly—but now I feel a larger charity for such. Your heart is big enough to feel all the force of that remark.—& so believing, you will not be surprised to find me thus boldly knocking at it. It does not seem to me that I am otherwise than moderate—it cannot seem so from my point of view—& so while I continue as moderate as I am now & have been, I think it is fair to hope that you will not turn away from me your countenance, or deny me your friendly toleration, even though it be under a mild protest."

"It is my desire as truly as yours, that sufficient time shall elapse to show you, beyond all possible question, what I have been, what I am, & what I am likely to be. Otherwise you could not be satisfied with me, nor I with myself." In defending his character, he cites his time on the West Coast and Hawaii, where his immersion into the local native culture led to additional doubts on the part of the Langdons: "I think that much of my conduct on the Pacific Coast was not of a character to recommend me to the respectful regard of a high eastern civilization, but it was not considered blameworthy there, perhaps. We go according to our lights. […] I think all my references can say I never did anything mean, false or criminal. They can say that the same doors that were open to me seven years ago are open to me yet; that all the friends I made in seven years, are still my friends; that wherever I have been I can go again—& enter in the light of day & hold my head up; that I never deceived or defrauded anybody, & don’t owe a cent. And they can say that I attended to my business with due diligence, & made my own living, & never asked anybody to help me do it, either. All the rest they can say about me will be bad. I can tell the whole story myself, without mincing it, & will if they refuse."

Clemens requests to "add to the references I gave Mrs. Langdon," providing a lengthy list off the many "friends" he made out west, including John Neely Johnson (1725-1872) of Carson City, Nevada ("was Governor of California some ten years ago & is now Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Nevada" and for some time his next door neighbor; Henry Goode Blasdel (1825-1900), the first governor of Nevada ("he has known me four or five years—don’t know whether he has known any good of me or not. He is a thoroughly pure & upright man"); Joseph T. Goodman, ("raised in Elmira, I belive … Chief editor of the 'Daily Enterprise', Virginia City") and Goodman's News-Editor, Putnam ("neither of whom would say a damaging word against me for love or money or hesitate to throttle anybody else who ventured to do it…"). In addition, Clemens refers Langdon to Lewis Leland (a hotel proprietor in New York, formerly of san Francisco's Occidental), and R. B. Swain of the San Francisco Mint: "the Schuyler Colfax of the Pacific Coast," a man "against whose pure reputation nothing can be said, although Clemens confesses, "he don't know much about me himself, but he ought to know a good deal through his secretary Frank B. [Bret] Harte (Editor of the Overland Monthly & the finest writer out there)" [Clemens has crossed out "one of the finest writers out there"] for we have been intimate for several years…" Quoting this portion of the letter, Justin Kaplan comments that "it was a curiously random, even self-defeating list … Clemens later said that he had left out close friends because he knew they would lie for him" (Kaplan, Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain, p. 90).

"As to what I am going to be, henceforth, it is a thing which must be proven & I am upon the right path—I shall succeed, I hope. Men as lost as l, have found a Saviour, & why not l? I have hope—an earnest hope—a long-lived hope" [a passage probably elicited by Langdon's criticism of instability and Clemens's rather inchoate religious beliefs]. Clemens offers additional details regarding his continuing lecture tour, his salary, and plans being considered to take over a Cleveland newspaper, then concludes by asking "pardon for past offences against yourself, they having been heedless, & not deliberate.. . He signs himself "With reverent love & respect."

The outcome is best narrated by Clemens himself. In early 1869, Mr. Langdon began to receive replies from the people he had been directed to by Clemens. "The results were not promising. All those men Were frank to a fault. They not only spoke in disapproval of me but they were quite unnecessarily and exaggeratedly enthusiastic about it. " When he and Jervis Langdon met to discuss the unflattering letters of reference, Langdon exclaimed, "'What kind of friends are these? Haven't you a friend in the world?' 'Apparently not,' I answered. 'Then he said: 'I'll be your friend myself. Take the girl. I know you better than they do.' Thus dramatically and happily was my fate settled" (The Autobiography of Mark Twain, ed. Charles Nieder, 1966, pp. 106-107). Published in The Love Letters of Mark Twain, ed. Dixon Wector, New York, 1949. Provenance: Clara Clemens Samossoud – Chester L. Davis (sale, Christie's New York, 17 May 1991, lot 82) – James S. Copley Library (sale, Sotheby's, New York, 17 June 2010, lot 461).

Try LotSearch and its premium features for 7 days - without any costs!

Be notified automatically about new items in upcoming auctions.

Create an alert