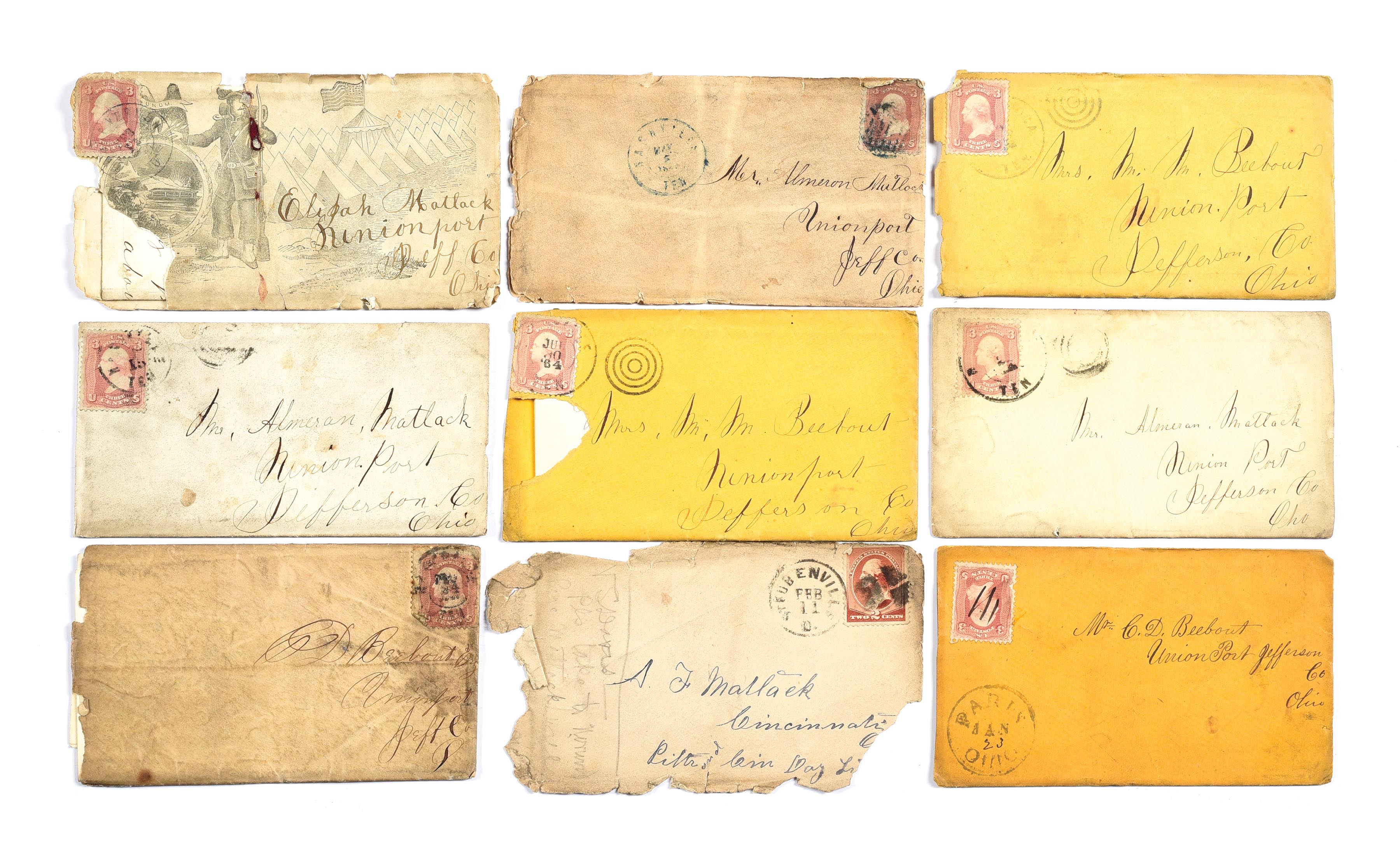

46 war-date and post-war documents, 3 CDVs. Captain Walter H. Wild began his service in the Union Army on April 17, 1861, a mere three days after the fall of Ft. Sumter. Enlisting as a corporal in the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery (3 months,) he was part of Patterson's Army of the Shenandoah. Unlike his brother Edward, a captain in the 1st Massachusetts Infantry, Walter missed the first battle of Bull Run. Re-enlisting in March 1862, Wild served in South Carolina with the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery as a bugler. On March 13, 1863, he was commissioned as first lieutenant of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a colored unit made famous in the film "Glory." On October 28, he was promoted to captain in the 36th US Colored Troops. However, he spent much of the latter part of the war as aide de camp to his brother, who had been promoted brigadier general and charged with raising and training black troops in North Carolina. While serving in General Wild's "African Brigade," Walter was wounded in the forehead at the battle of Wilson's Wharf. Legend has it that he had a silver plate the size of a silver half dollar implanted in his skull as a result. This archive contains several letters from Walter Wild that stretch from 1861 to 1866. It also contains letters from family members relating to the service of the Wild brothers, and concerning the elder Dr. Wild, who had suffered a stroke. In addition, it includes three CDVs taken in occupied Norfolk, VA. The first letters, from Wild’s service in the 1st RI Light Artillery, reveal his enthusiasm for soldiering, but also his jaded view with how the war was conducted. On May 12, 1862, Walter sees his first colored troops in Federal service: They have already begun organizing a black regiment with white officers here, similar to the Sepoys of India.Two companies were sent out the morn to drive in the contraband from the upper end of the island, able bodied men only. I shall be glad to see it done. They are a lazy saucy pack of hounds costing U.S. a pretty sum. By the summer of 1863, Walter was serving as Edward's only staff officer, as they tried to train, equip, and find white officers for the colored regiments they had been tasked to raise. The troops were eager and willing, and soon Walter believed they drilled as well as the troops in the 54th Massachusetts. What was holding them back was a lack of commissioned officers willing to lead black troops (whether from prejudice, or the fact that white officers captured leading black troops were summarily executed by the Rebels.) This situation was seen as an opportunity by ambitious lower ranks: However, this will not long be so for white men have condescended and even asked to become non commissioned officers with the prospect of promotion. On October 17, 1863, on Folly Island, SC, Capt. Wild notes they are Fighting in the old McClellan style with shovel and pick and axe and hatchet. Proud of the progress the free blacks and freed slaves had made, Wild states: I only wish we could exhibit our brigade today for a few hours in any northern city, and if we did not satisfy the most incredulous of our efficiency would willingly hide my diminished head (a reference to the piece of his skull missing after being wounded in the head at Wilson's Wharf).

46 war-date and post-war documents, 3 CDVs. Captain Walter H. Wild began his service in the Union Army on April 17, 1861, a mere three days after the fall of Ft. Sumter. Enlisting as a corporal in the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery (3 months,) he was part of Patterson's Army of the Shenandoah. Unlike his brother Edward, a captain in the 1st Massachusetts Infantry, Walter missed the first battle of Bull Run. Re-enlisting in March 1862, Wild served in South Carolina with the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery as a bugler. On March 13, 1863, he was commissioned as first lieutenant of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, a colored unit made famous in the film "Glory." On October 28, he was promoted to captain in the 36th US Colored Troops. However, he spent much of the latter part of the war as aide de camp to his brother, who had been promoted brigadier general and charged with raising and training black troops in North Carolina. While serving in General Wild's "African Brigade," Walter was wounded in the forehead at the battle of Wilson's Wharf. Legend has it that he had a silver plate the size of a silver half dollar implanted in his skull as a result. This archive contains several letters from Walter Wild that stretch from 1861 to 1866. It also contains letters from family members relating to the service of the Wild brothers, and concerning the elder Dr. Wild, who had suffered a stroke. In addition, it includes three CDVs taken in occupied Norfolk, VA. The first letters, from Wild’s service in the 1st RI Light Artillery, reveal his enthusiasm for soldiering, but also his jaded view with how the war was conducted. On May 12, 1862, Walter sees his first colored troops in Federal service: They have already begun organizing a black regiment with white officers here, similar to the Sepoys of India.Two companies were sent out the morn to drive in the contraband from the upper end of the island, able bodied men only. I shall be glad to see it done. They are a lazy saucy pack of hounds costing U.S. a pretty sum. By the summer of 1863, Walter was serving as Edward's only staff officer, as they tried to train, equip, and find white officers for the colored regiments they had been tasked to raise. The troops were eager and willing, and soon Walter believed they drilled as well as the troops in the 54th Massachusetts. What was holding them back was a lack of commissioned officers willing to lead black troops (whether from prejudice, or the fact that white officers captured leading black troops were summarily executed by the Rebels.) This situation was seen as an opportunity by ambitious lower ranks: However, this will not long be so for white men have condescended and even asked to become non commissioned officers with the prospect of promotion. On October 17, 1863, on Folly Island, SC, Capt. Wild notes they are Fighting in the old McClellan style with shovel and pick and axe and hatchet. Proud of the progress the free blacks and freed slaves had made, Wild states: I only wish we could exhibit our brigade today for a few hours in any northern city, and if we did not satisfy the most incredulous of our efficiency would willingly hide my diminished head (a reference to the piece of his skull missing after being wounded in the head at Wilson's Wharf).

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen