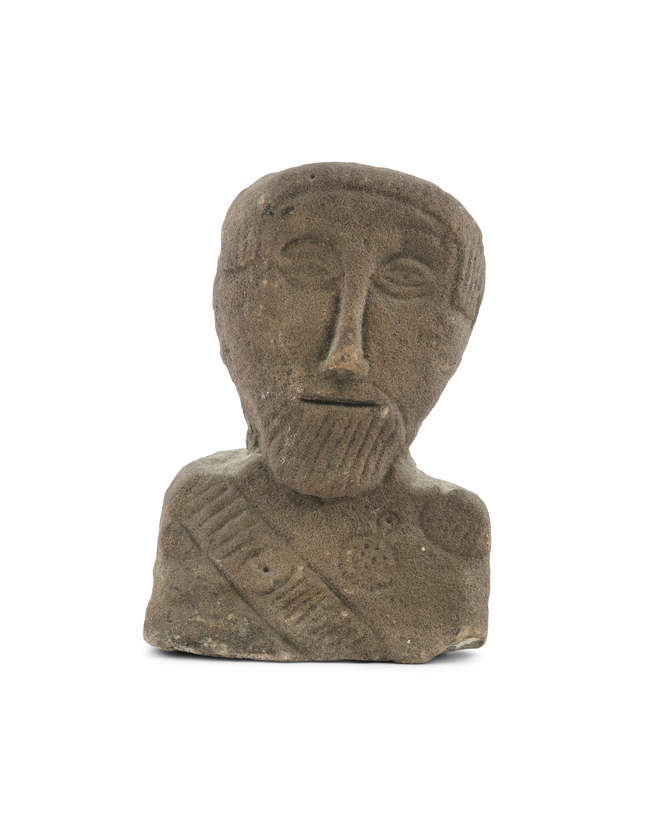

carved and weathered red sandstone, of powerful visage, with arched brows, deeply set eyes and broad triangular nose, the mouth bearing an enigmatic smile with a broad moustache covering the upper lip 24cm tall Provenance: Originally uncovered during the digging of a wall at Sharpcliffe Hall, Staffordshire, United Kingdom. The site is situated in the immediate vicinity of prehistoric structures uncovered by men working in a gravel pit in 1910. Subsequently part of a private collection, United Kingdom. Note: Stone votive heads are perhaps the most enigmatic of all the art produced by the Iron Age peoples of Britain, Ireland and continental Europe, often termed “Celts”. Frequently found near bodies of water, their function is not clear, suggestions have included their use as surrogates in head hunting societies, cult foci, or as venerated objects of healing. The ubiquity of the head motif sculpted in stone or carved in metal suggests that the ancient Britons held it in special reverence, likely believing it to be the centre of the soul. The present example epitomises the simple lines imbued with great power that defines ancient Celtic art. The individual depicted, whether deity or human subject, has an undeniable presence. The style of the finely backcombed hair and moustache, well-groomed and reaching across much of the face, bears a strong similarity to those seen on three small copper alloy models of men's faces uncovered at two Late Iron Age burials (c. 50 – 20 B.C.) in Welwyn in 1906 and now housed at the British Museum (accession number 1911,1208.5). The facial character depicted in both the present piece and the Welwyn fittings is reflected in the contemporaneous record of the Greek writer Diodorus Siculus when discussing the physical appearance of the Gauls, the British Celts continental cousins in the 1st century B.C.: “The Gauls are tall of body with rippling muscles and white of skin and their hair is blond, and not only naturally so for they also make it their practice by artificial means to increase the distinguishing colour which nature has given it. For they are always washing their hair in limewater and they pull it back from the forehead to the nape of the neck, with the result that their appearance is like that of Satyrs and Pans since the treatment of their hair makes it so heavy and coarse that it differs in no respect from the mane of horses. Some of them shave the beard but others let it grow a little; and the nobles shave their cheeks, but they let the moustache grow until it covers the mouth.” His haunting smile is relatively unusual, with a thin slit mouth more common amongst Celtic sculpture of the period. One notable parallel is the Hendy Head (displayed at Oriel Môn), discovered in a field on Anglesey during the 1950’s. Carved of red sandstone and dating to the late Iron Age, it likely depicts a Celtic deity worshipped at a local shrine, the mouth has a drilled opening to one side for libations and is formed into a similarly unsettling smile. The power of ancient Celtic art lies in its ability to sit between the recognisable and the otherworldly. The fact that this piece’s exact its meaning is lost to us perhaps adds to this ethereal quality.

carved and weathered red sandstone, of powerful visage, with arched brows, deeply set eyes and broad triangular nose, the mouth bearing an enigmatic smile with a broad moustache covering the upper lip 24cm tall Provenance: Originally uncovered during the digging of a wall at Sharpcliffe Hall, Staffordshire, United Kingdom. The site is situated in the immediate vicinity of prehistoric structures uncovered by men working in a gravel pit in 1910. Subsequently part of a private collection, United Kingdom. Note: Stone votive heads are perhaps the most enigmatic of all the art produced by the Iron Age peoples of Britain, Ireland and continental Europe, often termed “Celts”. Frequently found near bodies of water, their function is not clear, suggestions have included their use as surrogates in head hunting societies, cult foci, or as venerated objects of healing. The ubiquity of the head motif sculpted in stone or carved in metal suggests that the ancient Britons held it in special reverence, likely believing it to be the centre of the soul. The present example epitomises the simple lines imbued with great power that defines ancient Celtic art. The individual depicted, whether deity or human subject, has an undeniable presence. The style of the finely backcombed hair and moustache, well-groomed and reaching across much of the face, bears a strong similarity to those seen on three small copper alloy models of men's faces uncovered at two Late Iron Age burials (c. 50 – 20 B.C.) in Welwyn in 1906 and now housed at the British Museum (accession number 1911,1208.5). The facial character depicted in both the present piece and the Welwyn fittings is reflected in the contemporaneous record of the Greek writer Diodorus Siculus when discussing the physical appearance of the Gauls, the British Celts continental cousins in the 1st century B.C.: “The Gauls are tall of body with rippling muscles and white of skin and their hair is blond, and not only naturally so for they also make it their practice by artificial means to increase the distinguishing colour which nature has given it. For they are always washing their hair in limewater and they pull it back from the forehead to the nape of the neck, with the result that their appearance is like that of Satyrs and Pans since the treatment of their hair makes it so heavy and coarse that it differs in no respect from the mane of horses. Some of them shave the beard but others let it grow a little; and the nobles shave their cheeks, but they let the moustache grow until it covers the mouth.” His haunting smile is relatively unusual, with a thin slit mouth more common amongst Celtic sculpture of the period. One notable parallel is the Hendy Head (displayed at Oriel Môn), discovered in a field on Anglesey during the 1950’s. Carved of red sandstone and dating to the late Iron Age, it likely depicts a Celtic deity worshipped at a local shrine, the mouth has a drilled opening to one side for libations and is formed into a similarly unsettling smile. The power of ancient Celtic art lies in its ability to sit between the recognisable and the otherworldly. The fact that this piece’s exact its meaning is lost to us perhaps adds to this ethereal quality.

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen